Advanced, Overlooked Python Typing

There is a common debate in Python circles: if you want static typing, why choose Python to begin with? One should just pick a language that supports it natively. The argument has some merit, but it assumes a world where one can “just pick” a language. In reality, that is rarely how software gets written, and those choices are usually made by very few people long before the software system takes off.

Python became the default language for machine learning, and its popularity pulled it into many more domains than before. Typical teams in companies tend to over-optimize for “reusability” and “consistency,”1 and increasingly adopt Python for application logic, internal tooling, orchestration, and other parts of the stack. In domains like these, one might desire strictly typed code, as it reduces the number of type-related unit tests, improves developer experience through typed autocomplete and code-generation tooling, and clarifies interfaces in fast-moving codebases.

Companies like Dropbox, Meta, and BlackRock report similar benefits from adopting typed Python. While quantitative evidence is scarce and difficult to trust in software research, some studies like Khan et al. (2021) suggest that type checking may prevent around 15% of defects in Python projects. Given this context, the goal of this article is to explore the often-overlooked advanced Python typing features that make large codebases more maintainable and pleasant to work in.

Disclaimer

As a whole, this article assumes Python 3.13 or newer. Several features used here, such as type statement and TypeIs, are only available in recent Python versions. The article also uses the modern bracket syntax for generics. In older versions of Python, you would write:

With the new bracket notation available in Python 3.12, the same code becomes more concise:

Assert Never

assert_never is a small utility that tells the type checker that a line of code should never be reached. At first it may seem unnecessary. It looks like you are writing extra code only to state that the code is unreachable. The benefit appears when you want to enforce exhaustiveness in conditionals and let the static type checker catch missing cases automatically. Consider the following example:

In some cases or domains, you might know that each variant must be handled separately. If the union is extended without adding new handling, you want the code to fail, ideally at type-check time. assert_never provides exactly this safety.

assert_never(arg) marks this branch as unreachable. If the union type is extended, the type checker detects that arg is no longer of type Never and reports an error. This gives you exhaustiveness checks at type-check time.

Internally, assert_never relies on the type Never, the bottom type in the Python type system. It represents a value that cannot exist. In a sound type system, an expression of type Never indicates a contradiction, which is why any reachable code path that passes a value to assert_never produces a type error.

Get Args

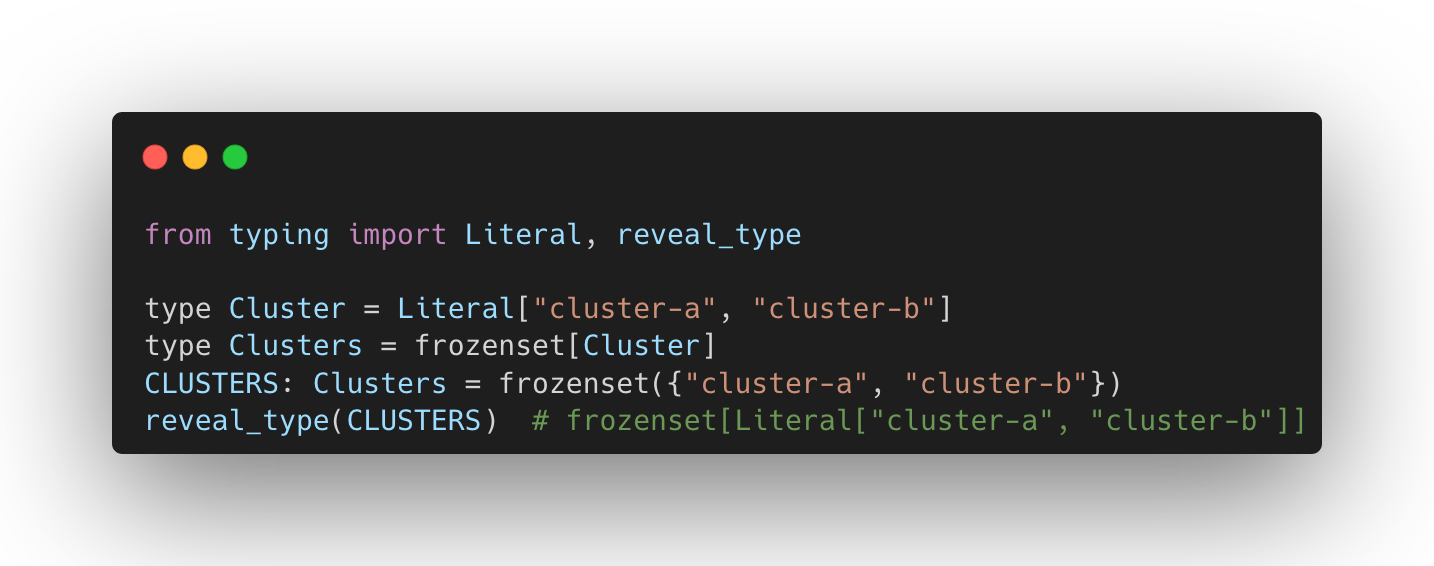

While not particularly advanced, get_args is a helpful tool that is often overlooked. A common anti-pattern involves defining a Literal type and then manually repeating those same values in a runtime variable. This forces you to maintain two lists in sync:

A cleaner approach uses get_args to extract values directly from the type definition. This ensures the Literal type serves as the single source of truth for both static checking and runtime logic:

TypedGuard

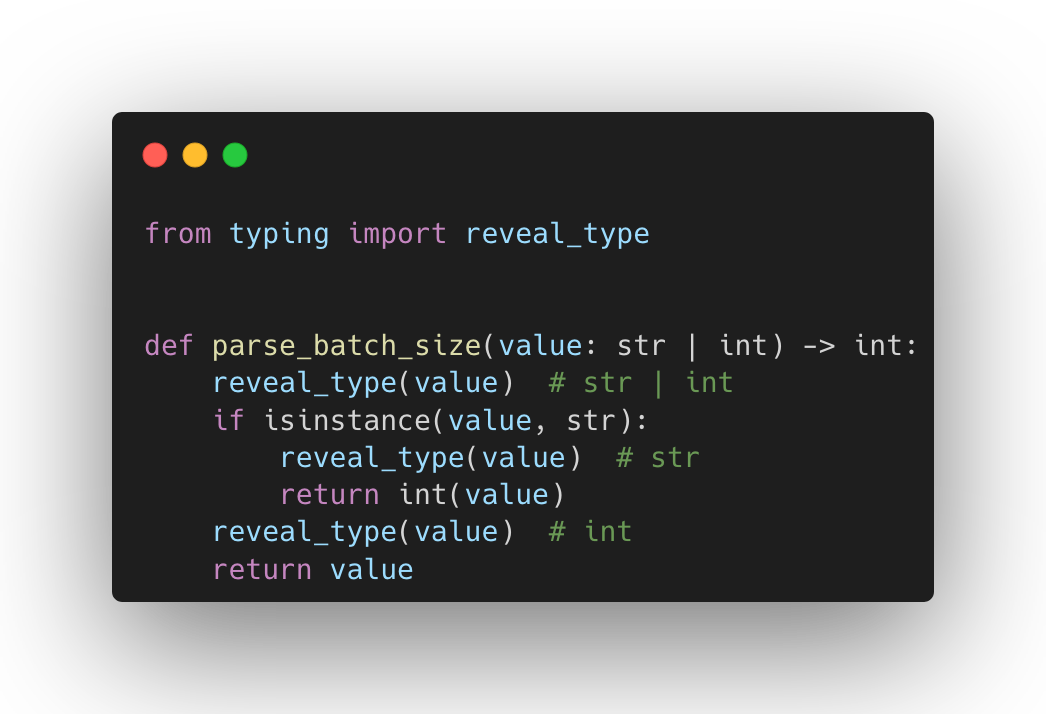

Conditional typing relies on type narrowing. When you check a condition such as isinstance, the type checker refines the type inside each branch (type narrowing). A union type becomes more specific step by step:

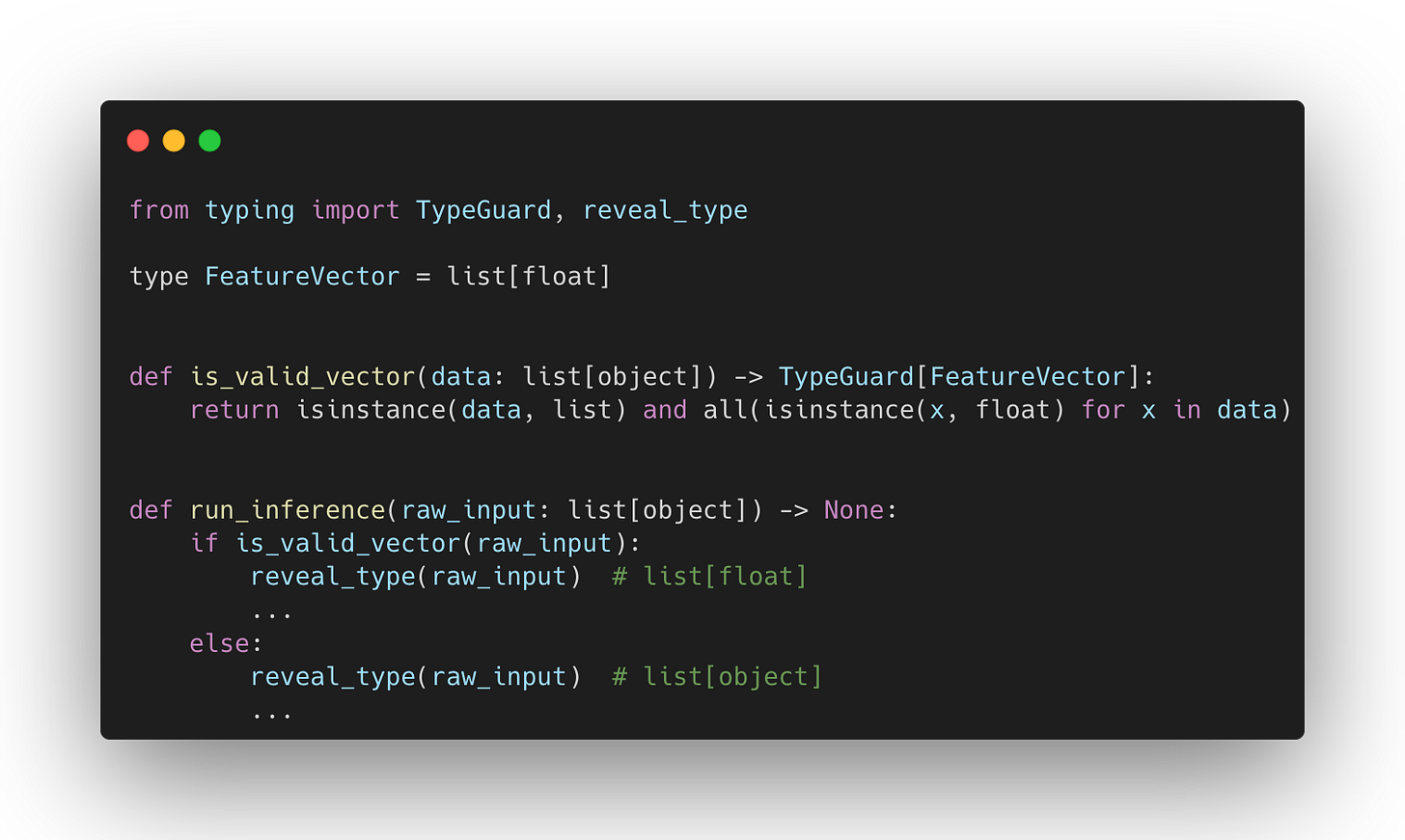

TypeGuard is feature that formalizes conditional typing for reusable predicates. While conditional typing relies on inline checks (like isinstance), TypeGuard lets you extract the type narrowing logic into a separate function that the type checker still understands:

TypeGuard is particularly valuable for handling mutable containers where standard covariance does not apply. For instance, list[float] is not a valid subtype of list[object] because it violates the Liskov substitution principle, as treating it as such would dangerously allow appending a string to a list of floats. However, TypeGuard enforces the target type on the positive branch arbitrarily. Because of this non-strict enforcement, it lacks the logic to narrow the type in the negative branch via set subtraction. This means the type checker learns nothing new if the check returns False, and this limitation is exactly why TypeIs was created.

TypeIs

TypeIs offers stricter and more precise type narrowing than TypeGuard by enabling bi-directional narrowing. However, because it relies on mathematical set subtraction to deduce types in the else branch, TypeIs requires that the narrowed type be a valid subtype (consistent with) the input type:

In short, use TypeIs by default for safe bidirectional narrowing on unions and subtypes, allowing the type checker to learn from both positive and negative cases. Reserve TypeGuard for structurally incompatible types due to invariance2, where TypeIs cannot perform negative narrowing (e.g., it cannot determine what ‘a list of objects minus a list of integers’ would be).

Overloading

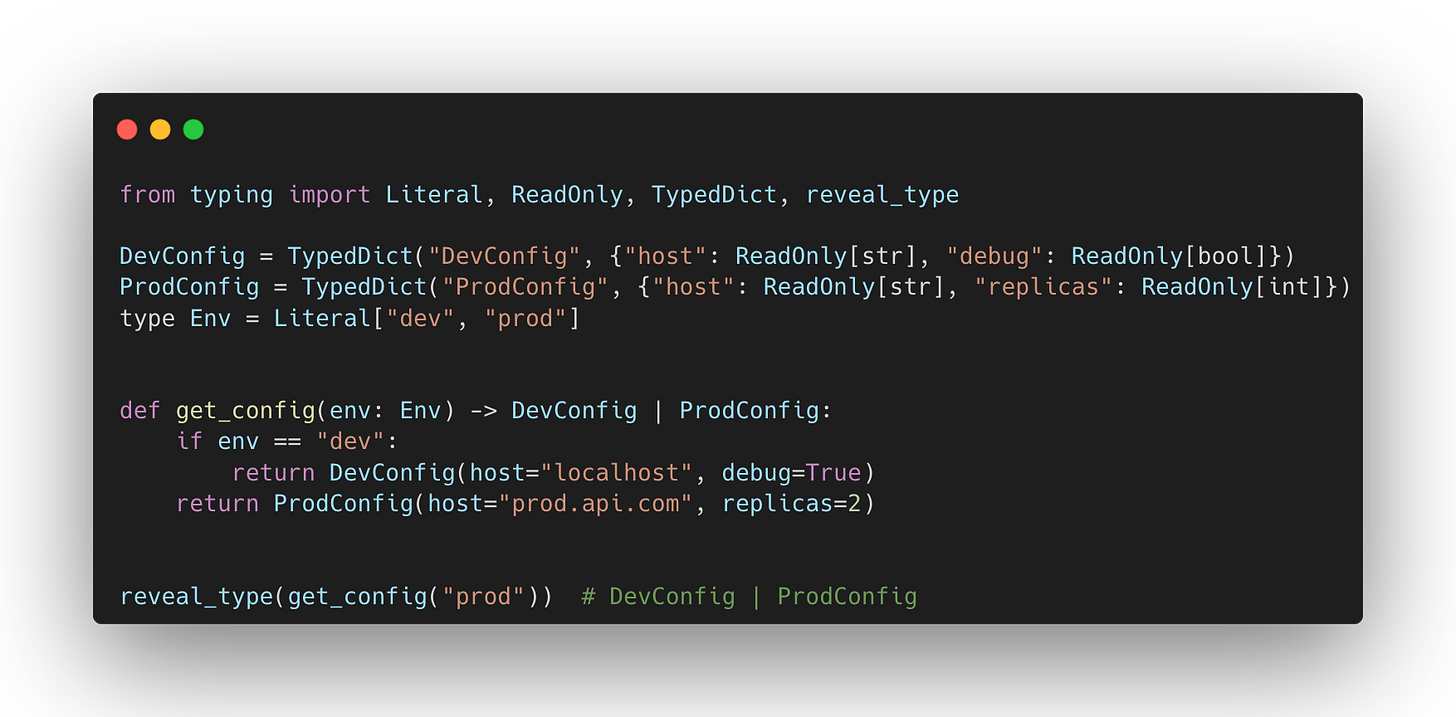

Quite often, functions return a union type, because different branches of code produce different types:

While the type checker correctly infers a union as the final return type, we often might know that the actual type depends on the argument used. Ideally, we want the type checker to discriminate the union based on the input, so that calling the function with a specific argument gives us a precise return type:

Overloading is essentially a structured form of conditional typing. It lets you declare multiple type signatures for a single function, where the return type is directly determined by the input value. In practice, this allows the type checker to perform precise narrowing at the call site. This means the caller gets a specific return type immediately, avoiding the need to perform additional isinstance checks on the result.

Unpack

Unpack lets you expand a mapping type into individual keyword arguments. It gives the type checker full visibility into which keys are required and what types their values must have. This makes functions that accept many related parameters easier to call and safer to work with, since missing or invalid arguments can be caught immediately:

Concatenate

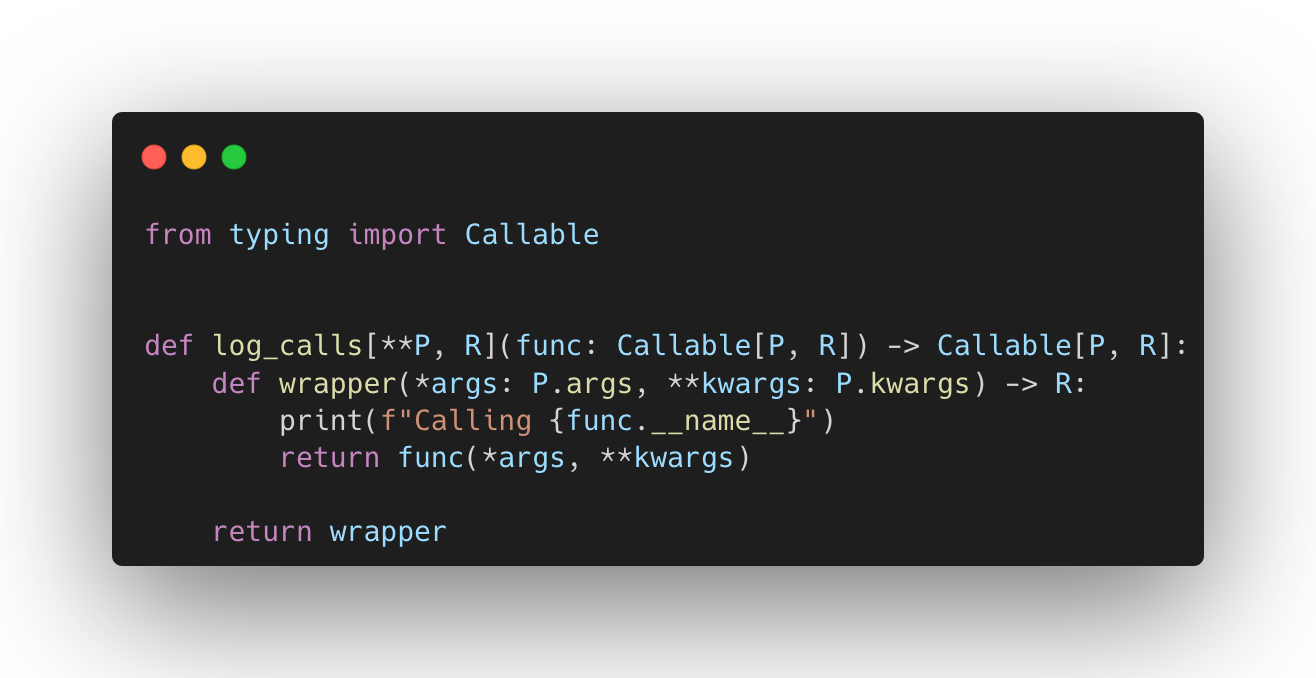

Decorators that modify a function’s signature are a common source of typing issues. They are often annotated as Callable[..., R], which discards the original parameter information. As a result, the type checker can no longer verify whether calls are valid:

In cases like this, the decorator changes the signature by removing the logger parameter from the public interface and injecting it automatically when the function is called. You can try to annotate such a decorator more strictly, but this often requires hard-coding a specific parameter signature or creating multiple overloads. Both options reduce the generality of the decorator. Concatenate solves this problem by letting you describe exactly how the decorator changes the function’s parameters:

Concatenate[logging.Logger, P] tells the type checker that the wrapped function expects a Logger as the first parameter and the parameters captured by P after that. P is a ParamSpec that includes both positional and keyword parameters. The return type Callable[P, R] indicates that the wrapper exposes only the parameters in P to the caller. The logger is provided internally and does not appear in the public interface. This allows the type checker to understand how the decorator reshapes the signature and to detect invalid calls.

Terms are in quotes because at that point “reusability” and “consistency” no longer mean what they should.

In physics, “invariant” refers to a property that remains constant despite changes in perspective, such as the speed of light. In type theory, “invariant” means that no matter how the inner types relate to each other, the relationship between the containers stays null.