Functional Programming Bits in Python

Beyond Map & Filter

Functional Programming (FP) practitioners might not like hearing Python and FP mentioned in the same context, as in Python:

Immutability can get expensive because it lacks standard-library persistent data structures with structural sharing.

Recursion is a tricky substitute for loops, since Python does not optimize tail calls.1

Referential transparency is a bit of a chore because you have to manually isolate pure logic from “effects” like mutation, global state, and exceptions.

There is a firm division between expressions and statements, whereas in a pure FP language everything is an expression.

Python simply lacks FP-friendly syntactic ergonomics.

Still, you can treat FP paradigms as a pragmatic toolkit and apply them where they fit. In practice, that might mean using higher-order functions to specialize and compose behavior, enabling ad-hoc polymorphism through generic function dispatch, reaching for point-free transformations when they make code more ergonomic, etc. This article takes that approach and covers a few often overlooked FP techniques in Python.

Disclaimer: The code shown below uses Python 3.14, and types are validated against MyPy 1.19.1.

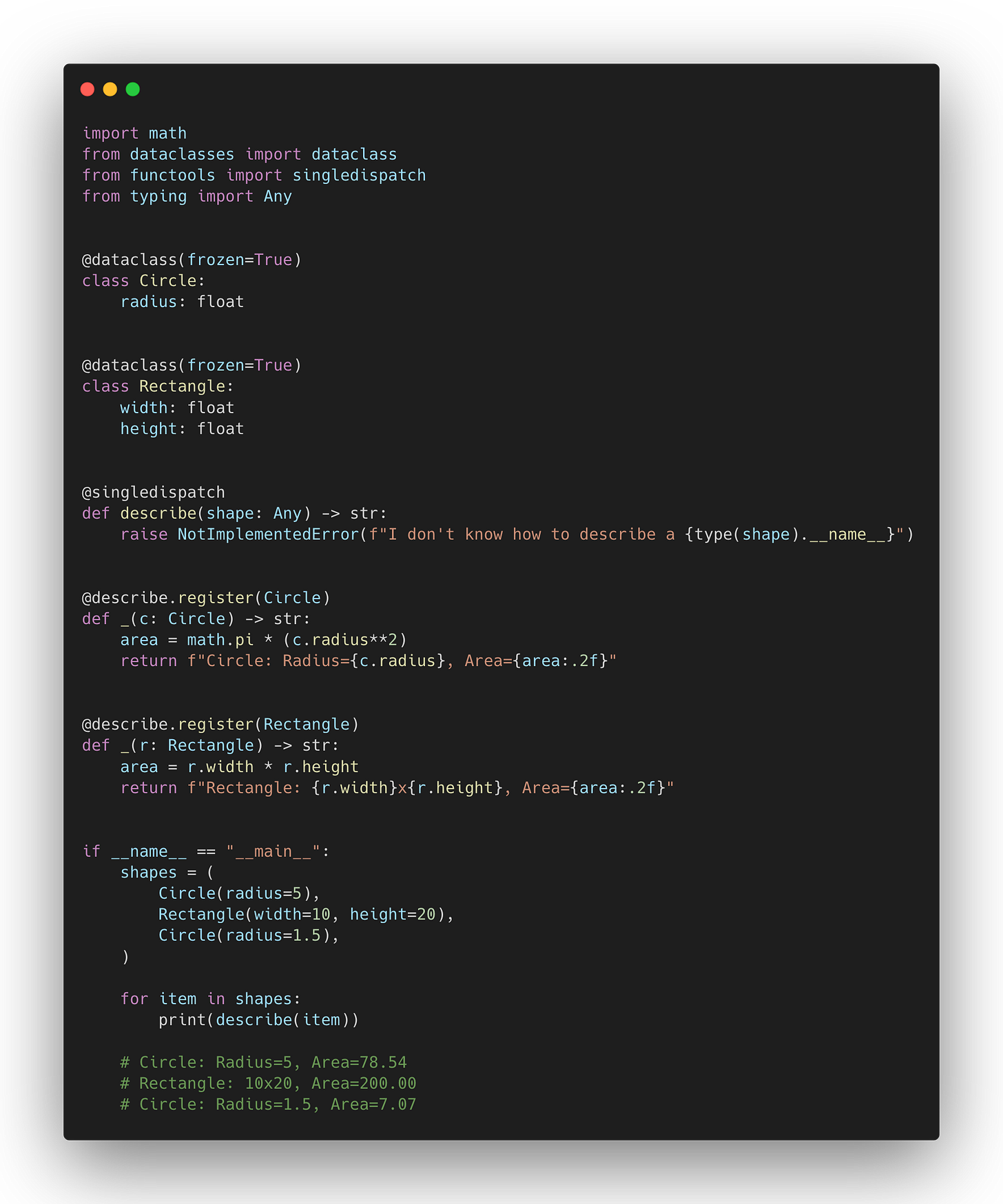

Ad-hoc Polymorphism & singledispatch

It is very common to see Python code relying on imperative isinstance checks (or match/case blocks in newer codebases) to handle different data types. While often preferred for small blocks due to readability and locality (data close to behaviour), this approach can create a “closed system”. Every time you introduce a new data type, you are forced to modify the original central function. If that function lives in a third-party library, extension might become impossible without fragile monkey-patching. In such a situation, one could argue this contradicts the Open-Closed Principle, as the logic is never truly closed for modification or fully open for extension.

singledispatch offers a functional alternative via ad-hoc polymorphism. It transforms a function into a generic registry that routes execution based on the type of the first argument. This mimics the function overloading and type class behavior found in languages like Haskell. Instead of a hard-coded switch block, you register independent handlers for specific types. It allows you to add support for new data structures in separate modules without ever touching the original base function. Brett Slatkin covers this in greater detail at PyCon US 2025.

singledispatch is a helpful option for modular designs. However, it should be used with care, as the added abstraction can be unnecessary for code that does not require such extension. For logic encapsulated within a class, singledispatchmethod provides this same polymorphic power for instance methods.

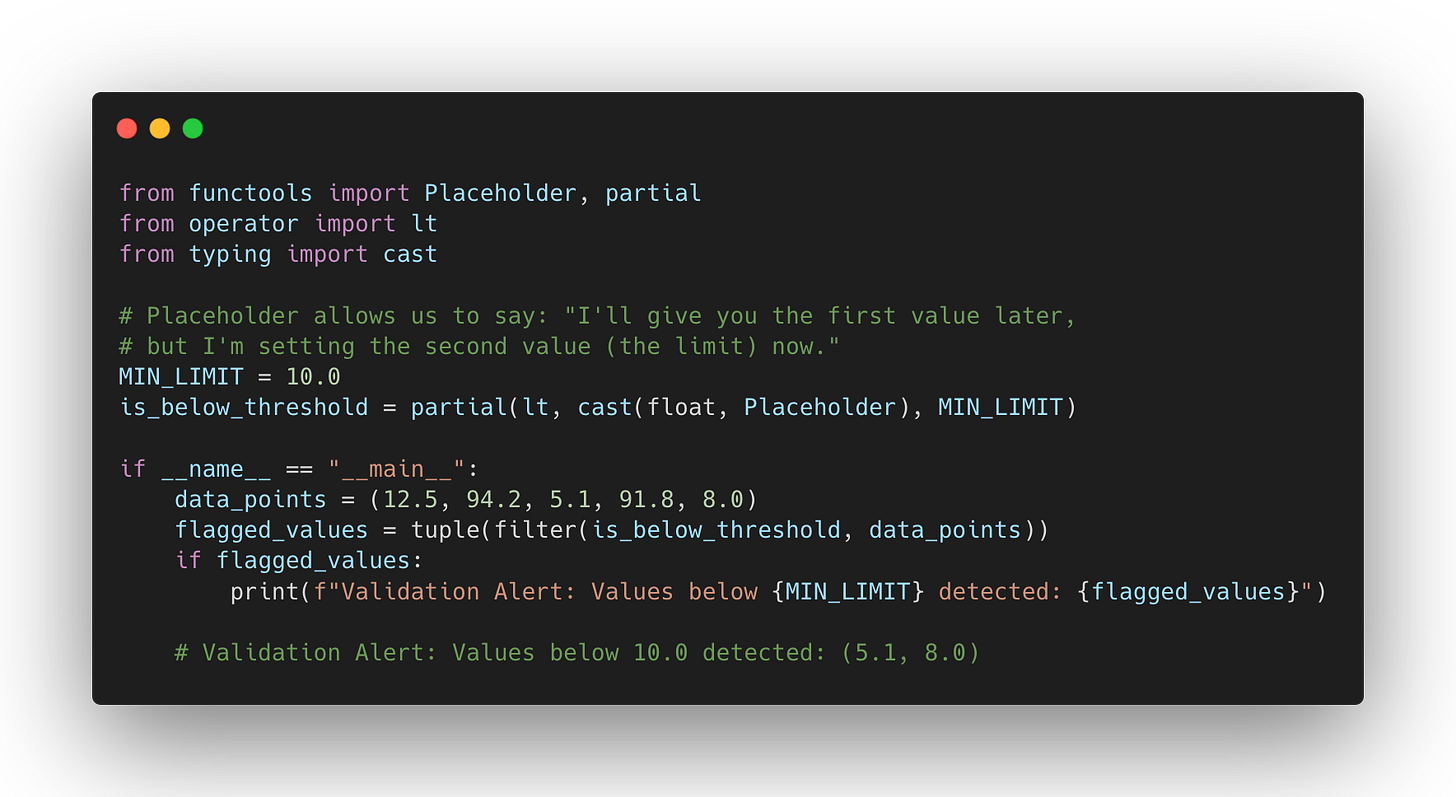

Partial Application & partial

Partial application is a functional technique that fixes a subset of a function’s parameters to produce a new callable of lower arity. It binds a general n-ary function to a specific context by “freezing” certain arguments into a persistent state.

This mechanism is useful for interface matching and higher-order composition. It allows a function to be reshaped to fit the signature required by a consumer, such as converting a binary function into a unary predicate for a filter. The placeholder sentinel further improves this through non-contiguous positional binding, maintaining intuitive logic without lambda boilerplate or the need to reverse operators to satisfy positional requirements.

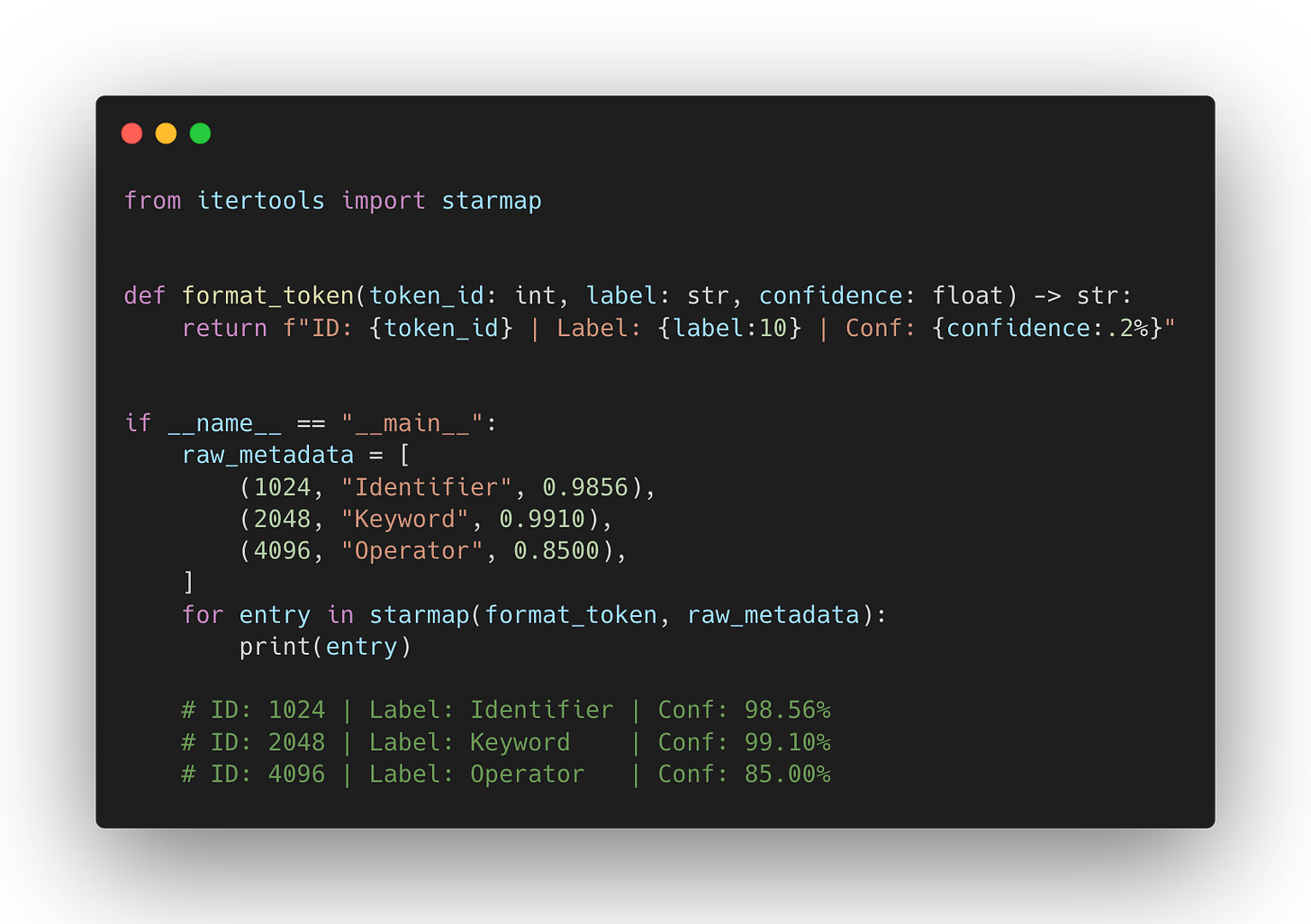

Arity Alignment & starmap

Data frequently arrives encapsulated in product types after zipping or grouping operations. Standard map implementations expect a unary projection, causing a signature mismatch if the downstream consumer is an n-ary function. While a lambda can manually destructure these types, it introduces boilerplate and obscures declarative intent within the pipeline.

starmap provides arity alignment by automatically unpacking tuple elements into a function's positional parameters. It acts as a formal bridge for higher-order composition, allowing n-ary logic to consume product types directly. This offloads argument distribution to the iterator protocol, decoupling data structure from functional logic.

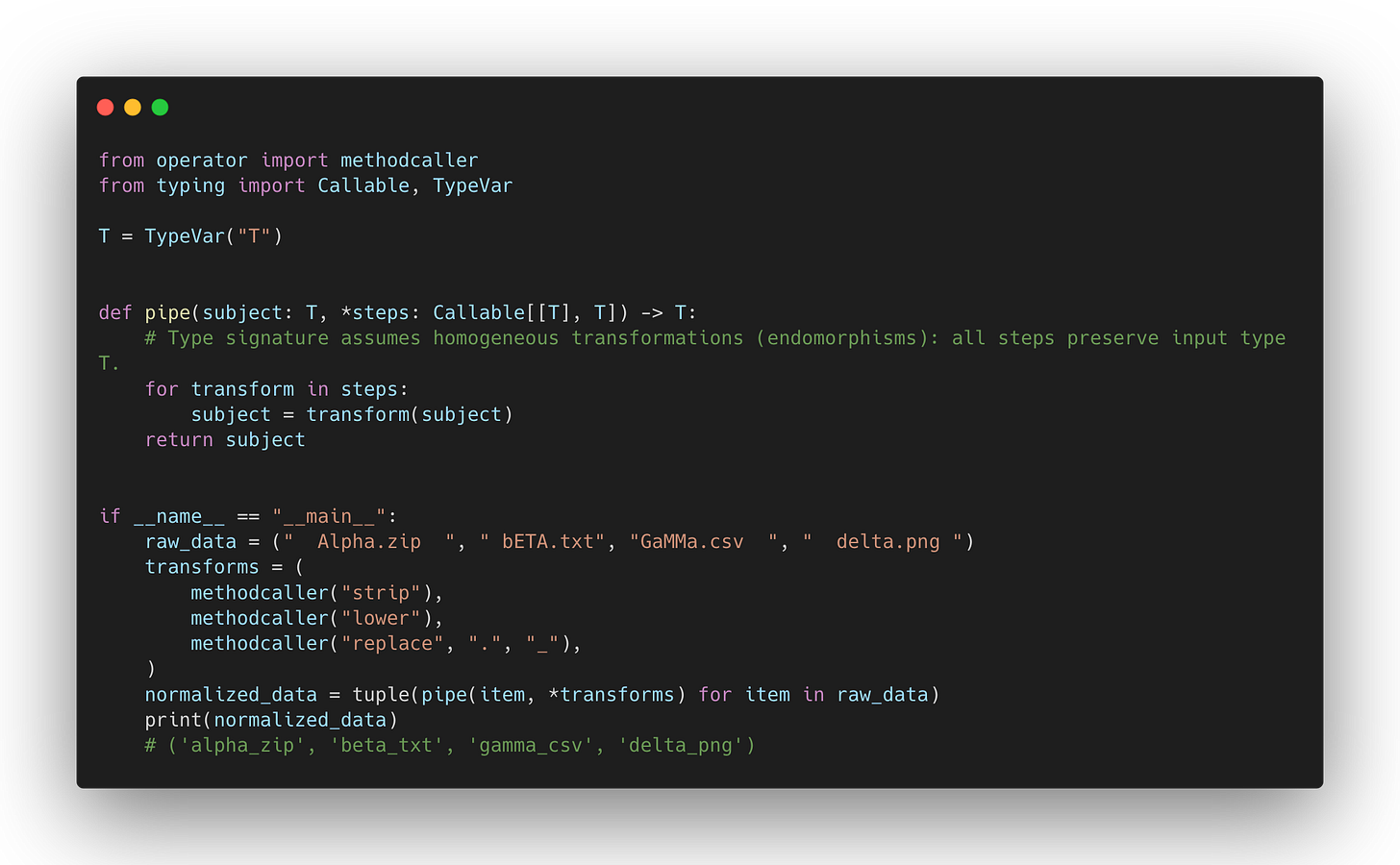

Tacit Programming & methodcaller

operator.methodcaller facilitates tacit (point-free) programming by allowing you to define operations without explicitly naming their data inputs. It “lifts” an object method into a standalone function that accepts the target object as its initial argument, effectively decoupling the action from the data. This allows for the construction of functional pipelines where the data is implied rather than manually passed through named variables.

From a design perspective, this approach is most effective when a variable name in a lambda adds no semantic value/serves as “syntactic noise” and when the method name itself clearly communicates the intent. It works the best in declarative sequences where the reader’s focus should remain on the flow of transformations rather than the mechanics of the call. However, this style should be used carefully. While it reduces boilerplate, it requires the reader to be comfortable with the functional paradigm to maintain clarity.

Unfortunately, the standard library lacks a native pipe or compose utility, which is needed for a tacit programming style. While a basic implementation is simple, a truly generic version that doesn’t assume endomorphisms is a bit trickier.

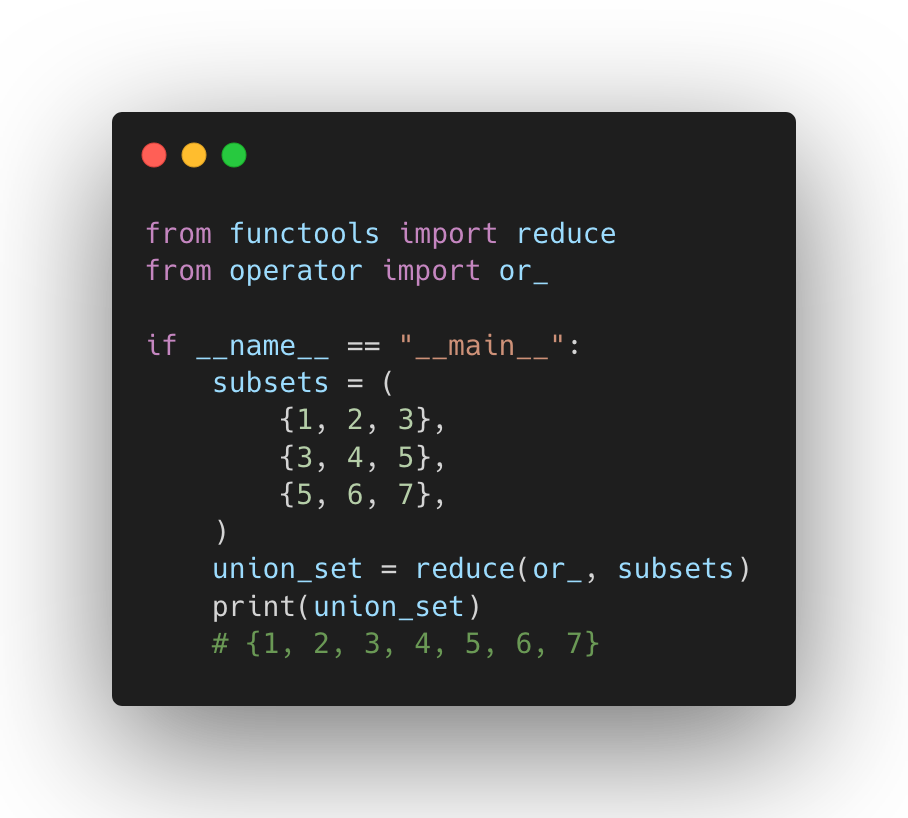

Catamorphism & reduce

A catamorphism is the general idea of folding a data structure into a single value. In functional terms, you take a structure apart while combining its pieces with a function. In Python, this usually looks like starting with a seed value and repeatedly merging it with each element to update an accumulator.

reduce is the standard left fold that does exactly that. It applies a function to an accumulator and the next item in the iterable, then carries the result forward. It is a direct way to turn a sequence into one result, like a sum or a single combined object.

Even though reduce is a functional staple, it is somewhat controversial in Python. Guido van Rossum moved it to functools to steer people toward explicit loops or purpose-built helpers like sum(), any(), and all() (old interview from 2013):

There are some places where map() and filter() make sense, and for other places Python has list comprehensions. I ended up hating reduce() because it was almost exclusively used (a) to implement sum(), or (b) to write unreadable code. So we added builtin sum() at the same time we demoted reduce() from a builtin to something in functools (which is a dumping ground for stuff I don't really care about :-).

Still, it can be the more ergonomic choice in some implementations, especially when a fold or function pipeline reads cleaner as a single reduction than as a imperative loop.

Wrap-Up

Hence the title “Functional Programming Bits in Python”, with an emphasis on “bits”. When I thought about writing this small piece, I had the impression it would be larger, but for standard Python there simply wasn’t that much, in the end, that I wanted to include. It’s not a language that leans heavily into FP concepts, and that likely will not change anytime soon. That is mostly by design, with real trade-offs, as the benevolent dictator of Python put it many years ago:

If I think of functional programming, I mostly think of languages that have incredibly powerful compilers, like Haskell. For such a compiler, the functional paradigm is useful because it opens up a vast array of possible transformations, including parallelization. But Python's compiler has no idea what your code means, and that's useful too. So, mostly I don't think it makes much sense to try to add "functional" primitives to Python, because the reason those primitives work well in functional languages don't apply to Python, and they make the code pretty unreadable for people who aren't used to functional languages (which means most programmers).

Python avoids TCO to preserve the stack traces required for effective debugging. This reflects Guido van Rossum’s design philosophy that explicit loops are more readable for linear logic, whereas recursion should be reserved for naturally shallow structures like tree traversals.