InfiniBand and High-Performance Clusters

Fat-tree topologies, credit-based flow control, RDMA, and SHARP reductions

In the early 2000s, Mellanox published “Introduction to InfiniBand”, arguing that while Moore’s Law keeps improving chips, overall system performance is ultimately bound by Amdahl’s Law, meaning CPUs, memory bandwidth, and I/O must scale together. Conventional interconnects were not keeping up at the time, so InfiniBand proposed a switch-based serial fabric that unified data center communications, replacing fragmented I/O subsystems with a high-bandwidth, scalable interconnect. Fast forward to 2020, NVIDIA acquired Mellanox for ~$6.9 billion. This was the largest acquisition in NVIDIA’s history at that time. Quoting Jensen Huang:

With Mellanox, the new NVIDIA has end-to-end technologies from AI computing to networking, full-stack offerings from processors to software, and significant scale to advance next-generation data centers.

Closing the deal about two and a half years before ChatGPT’s release gave NVIDIA an end-to-end High Performance Computing (HPC) stack just as the industry was about to pivot to large-scale training. The timing was perfect, as at a trillion-parameter scale, interconnect bandwidth and tail latency often determine scaling efficiency of the entire cluster. In this post, we’ll briefly skim through1 InfiniBand’s design philosophy across different system levels and bring those pieces together to see how they fit to deliver incredible interconnect performance.

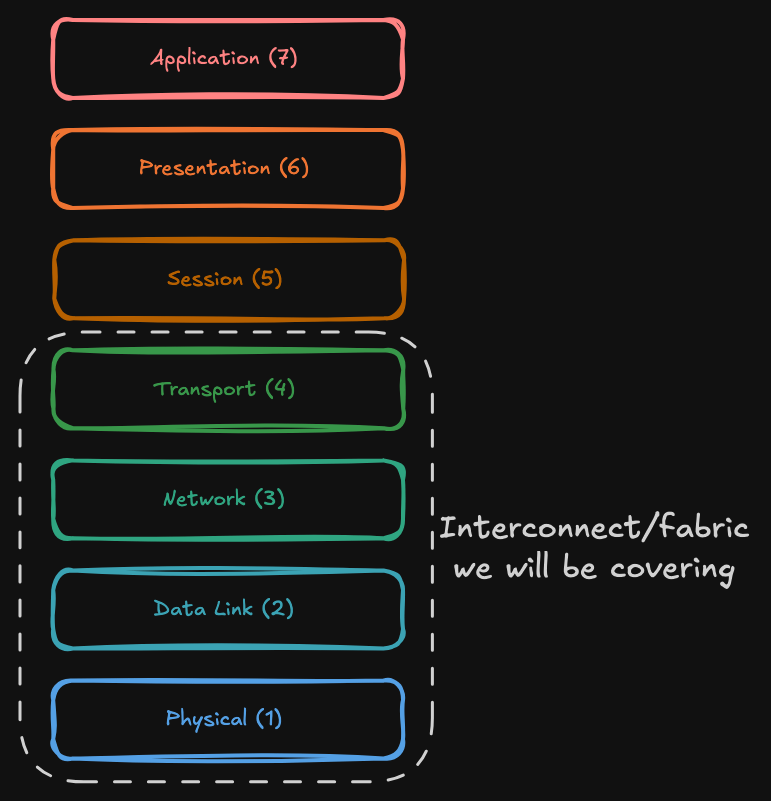

Philosophy Across the OSI Layers

The Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) model splits networking into seven layers to standardise how systems communicate, organising responsibilities from the physical link up to the application so components can evolve independently:

InfiniBand was built for HPC, so it avoids the classic Ethernet/TCP/IP model in which the host CPU handles most transport work. Even with modern Network Interface Card (NIC) offloads like checksum and segmentation, standard Ethernet stacks still leave core transport semantics in the host, such as connection state, ordering, and loss recovery, which makes the CPU a bottleneck for large-scale data movement. InfiniBand’s philosophy was to minimise redundant data paths by pushing transport and reliability into the hardware, and in some cases, pushing coordination work into the fabric itself.

Physical Layer

In terms of hardware, modern Ethernet and InfiniBand share many of the same physical building blocks: high-speed serializers/deserializers (SerDes), optical modules, and PAM4 signalling. Those building blocks enable very fast InfiniBand generations, such as Next Data Rate (NDR, 400 Gb/s) and the newer eXtended Data Rate (XDR), which push 200 Gb/s per lane. In practice, that translates to 800 Gb/s on 4x ports and up to 1.6 Tb/s on 8x ports.

Where the two diverge is above the wires. They differ in link behaviour, congestion control, and the way end-to-end interoperability is validated. Ethernet is designed around broad, multi-vendor standardisation through IEEE specifications. InfiniBand, by contrast, is defined by the IBTA2 and is often deployed as a tightly integrated end-to-end stack to reach stricter performance targets.

At these extreme speeds, electrical signals become so small and fast that physical interference makes bit errors practically inevitable. To handle this, both technologies rely on Forward Error Correction (FEC), often using the Reed-Solomon (RS-FEC) algorithm.

FEC acts like a mathematical safety net: the sender adds a small amount of redundant “check data” to every packet. If the message arrives slightly scrambled, the receiver uses this extra information to reconstruct the original data on the fly. While this adds a tiny amount of latency to encode and decode the data, it is a necessary trade-off for a clean, stable link that avoids the massive delays of retransmitting lost packets.

Data Link Layer

This layer contains a core philosophical difference between Infiniband and Ethernet. Ethernet is historically a “best effort” network. When a switch queue fills, it drops packets and relies on higher layers to recover. To support high-performance workloads, some Ethernet deployments use Priority Flow Control (PFC) to create a lossless environment. Instead of dropping data, PFC allows switches to signal the sender to pause traffic, ensuring that critical Remote Direct Memory Access (RDMA) packets are not lost during periods of high congestion.

InfiniBand is natively lossless at the link level. It uses credit-based flow control to prevent drops from transient congestion: a sender only transmits if the receiver has explicitly advertised available buffer space. By handling error detection and local retransmission directly in the hardware, the fabric maintains a clean, reliable link without needing higher-layer intervention.

Network Layer

In Ethernet IP fabrics, routing is usually distributed. Switches learn reachability via BGP, sometimes alongside an interior protocol such as OSPF or IS-IS, and the network has to reconverge when links or devices change.

InfiniBand takes a more controlled approach. A central Subnet Manager discovers the topology, assigns addresses, and programs the forwarding tables across the whole fabric, so path selection is coordinated rather than emergent. This makes behaviour more deterministic and easier to tune for cluster workloads. It can also precompute multiple paths and use adaptive routing to steer around congestion hotspots, keeping collective traffic from piling onto the same links.

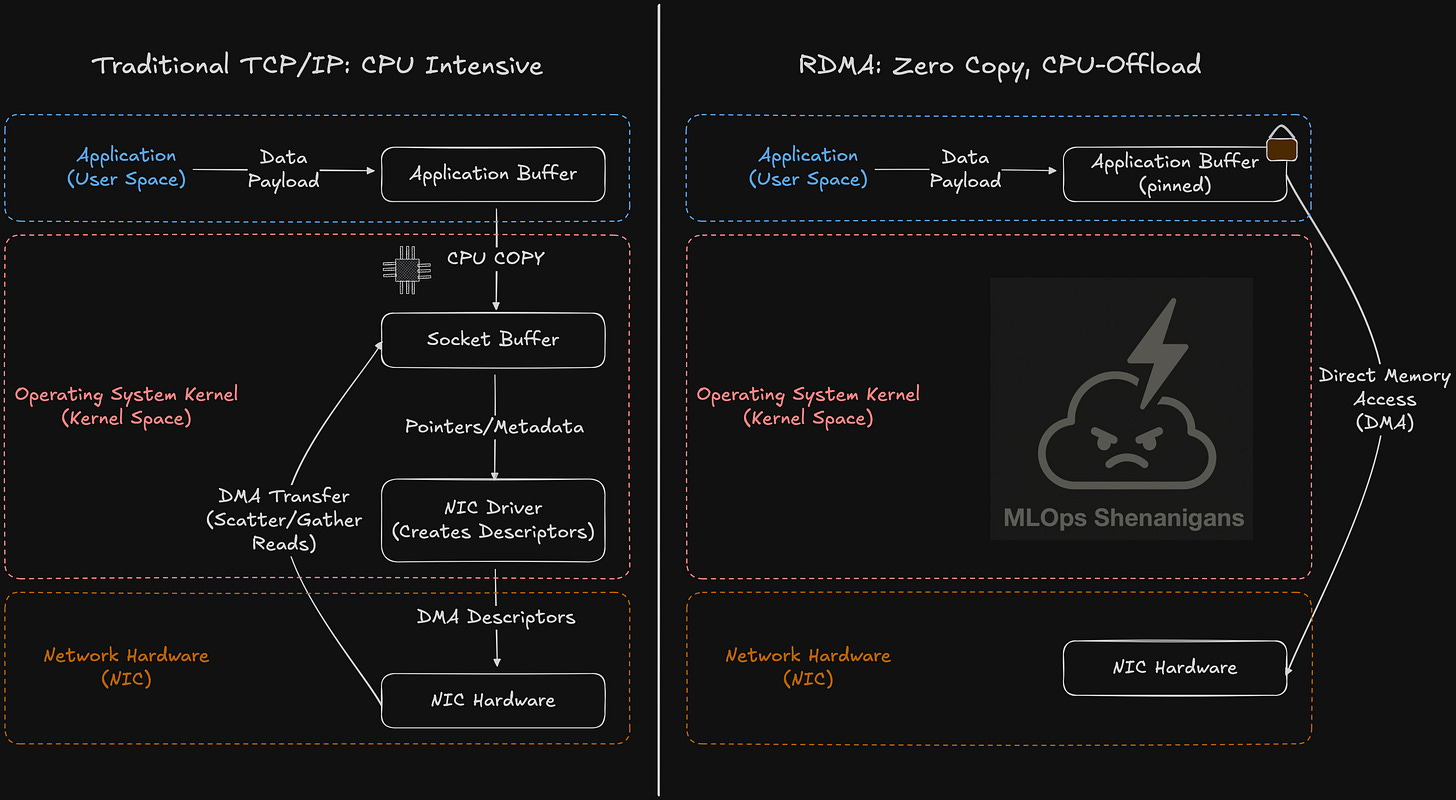

Transport Layer

In a traditional TCP/IP stack, the host CPU manages the transport lifecycle, which adds overhead from kernel crossings, interrupts, and extra data copies. InfiniBand avoids much of this by pushing transport and data movement into the NIC using RDMA. Ethernet can get to a similar programming model with RDMA over Converged Ethernet, most commonly RoCEv2. In both cases, the idea is the same: applications post work to NIC-managed queues, memory is registered up front, and the NIC uses DMA to move bytes directly between those regions with minimal kernel involvement and fewer copies.

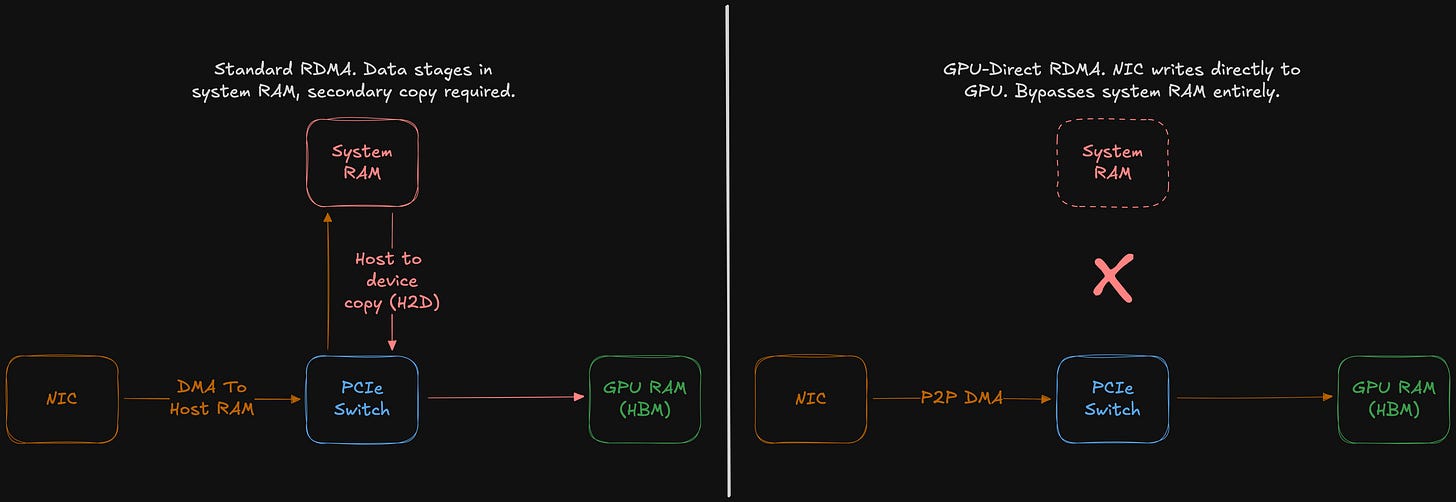

For GPU-heavy training, the remaining limitation of “standard” RDMA is that it first sends data to system RAM, which adds additional data staging and extra PCIe traffic when the real target is GPU memory. GPUDirect RDMA removes this inefficiency by allowing the NIC to DMA directly into GPU memory.

Similarly, GPUDirect Storage (GDS) shortens the data path between storage and GPU memory for bulk I/O, reducing bounce buffering through system RAM. The CPU still controls metadata and orchestration, but the bulk data path can become more direct.

In-Network Computing

In-network computing targets a key bottleneck in large clusters: collective communication, where thousands of nodes must synchronise and combine data for CPU (via MPI) or GPU (via NCCL) workloads. This paradigm is best realised by InfiniBand’s SHARP (Scalable Hierarchical Aggregation and Reduction Protocol). It pushes parts of reductions into the switch fabric, so the network aggregates data in flight3 instead of shuttling raw data between compute nodes.

Taken together, all these design decisions indicate that extreme performance is no longer possible within the strict boundaries of the classic OSI model. InfiniBand deliberately moves beyond the traditional "end-to-end" rules to prioritise efficiency. By minimising CPU involvement and treating the network as a coordinated system, it achieves speeds that isolated endpoints simply cannot match.

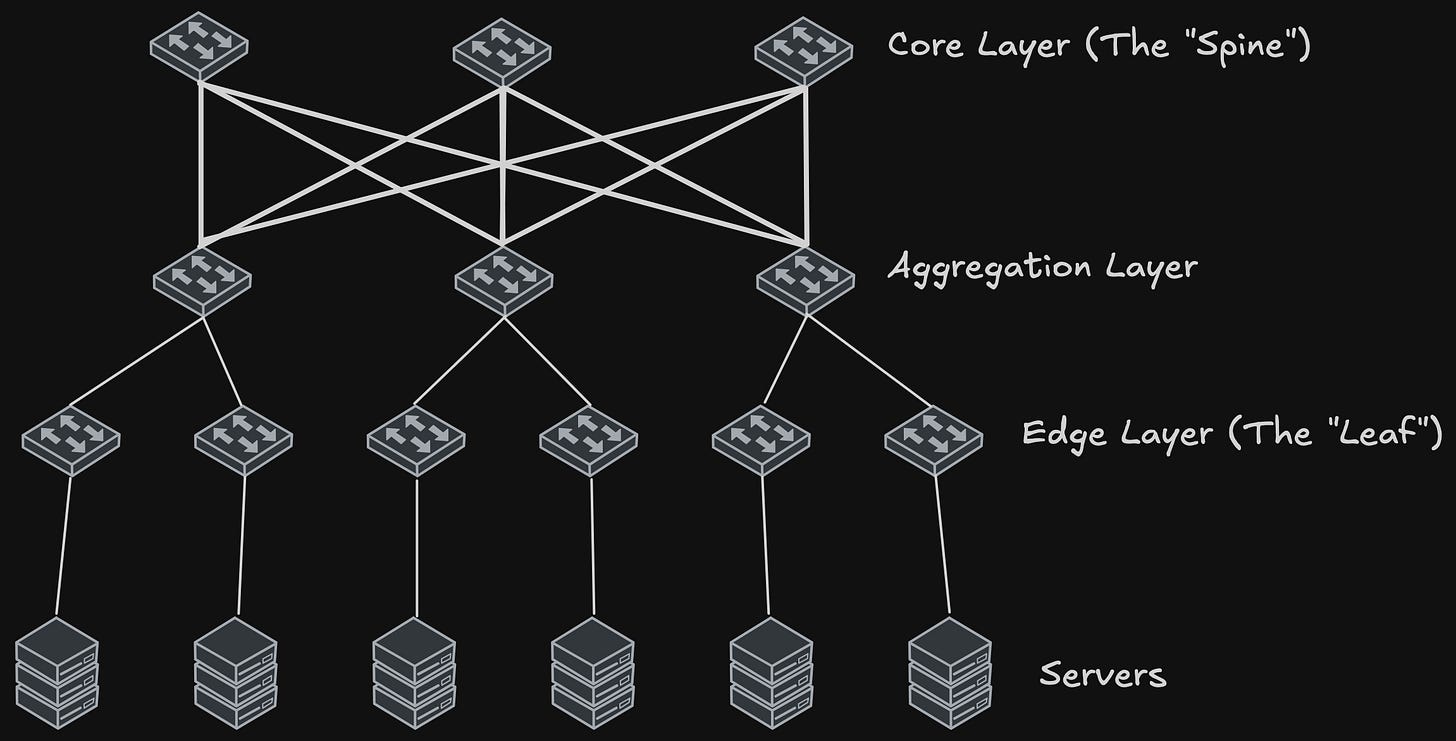

Network Topologies

When talking about performance, it’s also important to cover physical network topologies. The Fat Tree (Folded Clos) is the standard topology for HPC clusters because, when built without oversubscription, it delivers near-full bisection bandwidth. Its multiple equal-cost paths allow routing to spread load and avoid hotspots. This structure makes the entire cluster behave like a single, massive switch rather than a loose collection of bottlenecked cables. This is also why InfiniBand is often described as a “fabric”, since high path redundancy and unified management make the network operate as one system.

The main fat-tree trade-off is the massive cost of cabling and switching silicon required for a perfect 1:1 ratio. Engineers may choose other shapes for specific workloads:

Dragonfly: This splits the network into tightly coupled groups that link directly to one another. It is favoured for exascale systems because it minimises the number of expensive long-distance optical cables required to connect the whole machine.

3D Torus: This connects nodes in a cubic grid where each server links only to its X, Y, and Z neighbours. It is highly efficient for physics simulations where data mostly travels locally (neighbour-to-neighbour) rather than across the whole network.

Solving The Interconnect Bottleneck

Trillion-parameter models exceed the memory capacity of any single node, so weights and optimiser state must be sharded across machines using TP and FSDP:

Training becomes network-bound, and throughput is often gated by tail latency. During the backward pass, thousands of GPUs must synchronise gradients, and a single drop or transient hotspot can stall an entire step, leaving accelerators idle.

InfiniBand addresses this by strictly enforcing a zero-copy, CPU-bypass architecture. At the node level, RDMA allows the NIC to access memory without kernel involvement, while GPUDirect extends this efficiency by piping data straight into GPU HBM, skipping system RAM entirely. Inside the fabric, congestion is managed through credit-based flow control, adaptive routing, and SHARP reductions. Together, these features eliminate the micro-stalls that cause tail latency, allowing large clusters to operate near hardware peak rather than waiting on synchronisation.

InfiniBand’s long-standing dominance as the only viable option for high-performance clusters triggered an expected industry response: the formation of the Ultra Ethernet Consortium (UEC) on July 19, 2023. The goal of the UEC is straightforward: optimise Ethernet for high-performance AI and HPC networking, minimising changes to preserve interoperability while exceeding the performance of proprietary fabrics. With initial hyperscaler deployments expected in 2026, it will be interesting to see how UEC development and adoption unfold over time.

The IBTA Specification v2.0 consists of 2,156 pages. Trying to cover all concepts, even at a high level, would take quite some time. For this blog post, I’ve aimed to capture only a few design decisions at a very high level and very selectively.

The spec might be pretty expensive to get.

That’s why, when you run NCCL tests with SHARP enabled, you might see some surprising results: the reported effective bus bandwidth exceeding the physical link limits.